The economic vibes were never supposed to be this bad. In November 2024, Donald Trump won the presidency by capitalizing on higher costs and convincing voters he could deliver on a stronger economy. Voters fondly remembered the pre-2020 Trump economy and expected the Republican trifecta to deliver the economic growth and lower costs that were promised. As we head into 2026, the public has been sorely disappointed. What was an election-winning strength a year ago, as well as his biggest strength in his first term, has become a glaring liability.

Despite the outpouring of anecdotal reports any time someone brings it up, the economy isn’t doing that badly. Retail sales, consumer spending, and the stock market are holding steady or doing well. Unemployment, while creeping upward, is nowhere near crisis levels. Inflation has steadied at around 2.5-3.5% year-over-year, which is around the same as late 2024 and not close to the recent peak at 9.1% in 2022, nor the panicked hyperinflation consumers often claim. Interest rates have been elevated relative to pre-2022, but they’ve dropped over the last year. Real wages are up. GDP is up.

The American public does not agree. And I’d argue that their disagreement matters more than all of those nice macro stats put together.

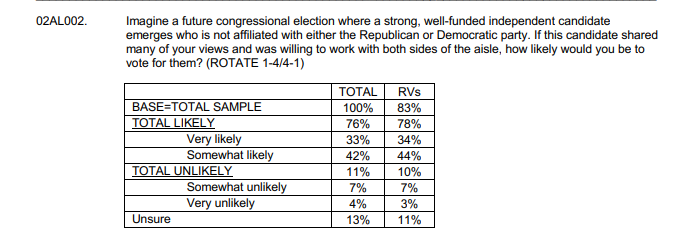

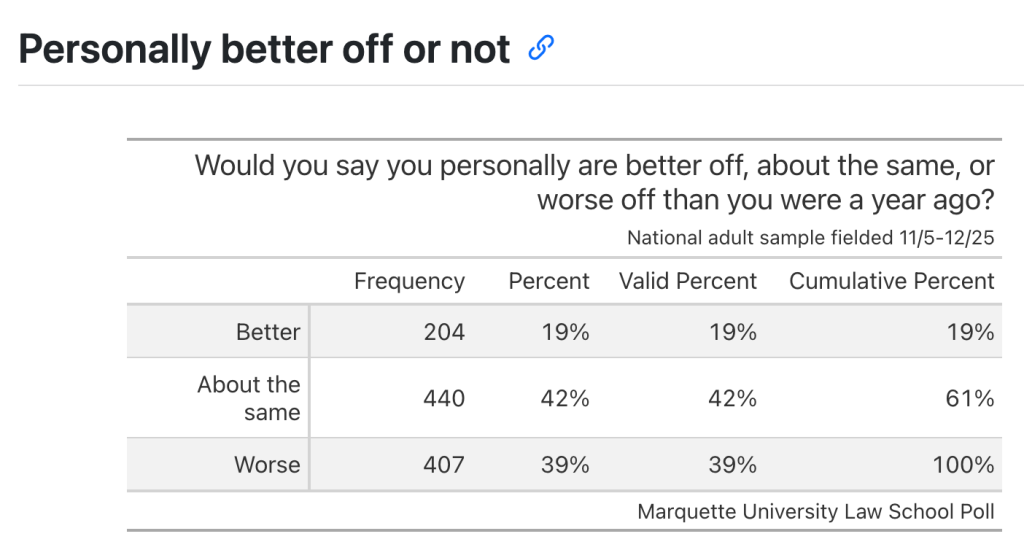

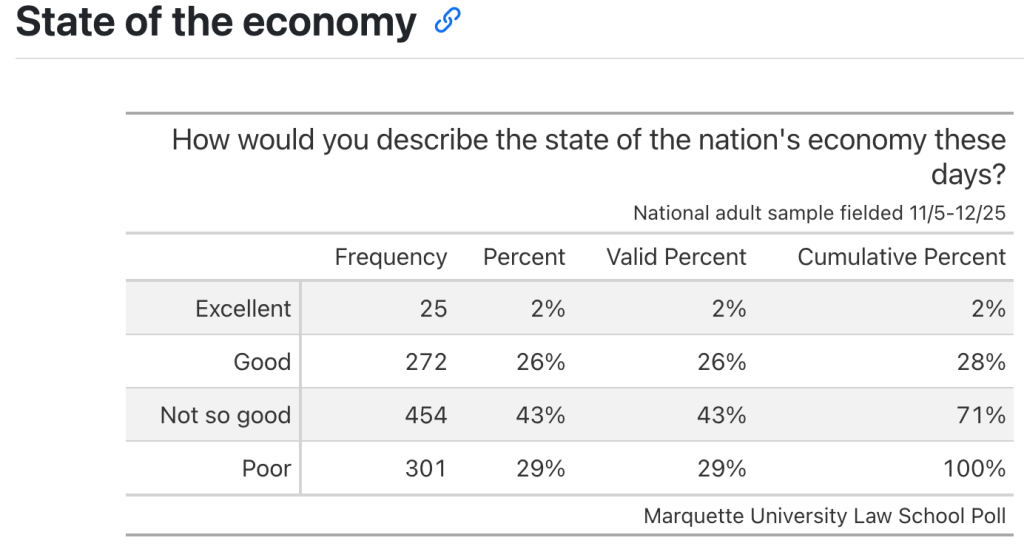

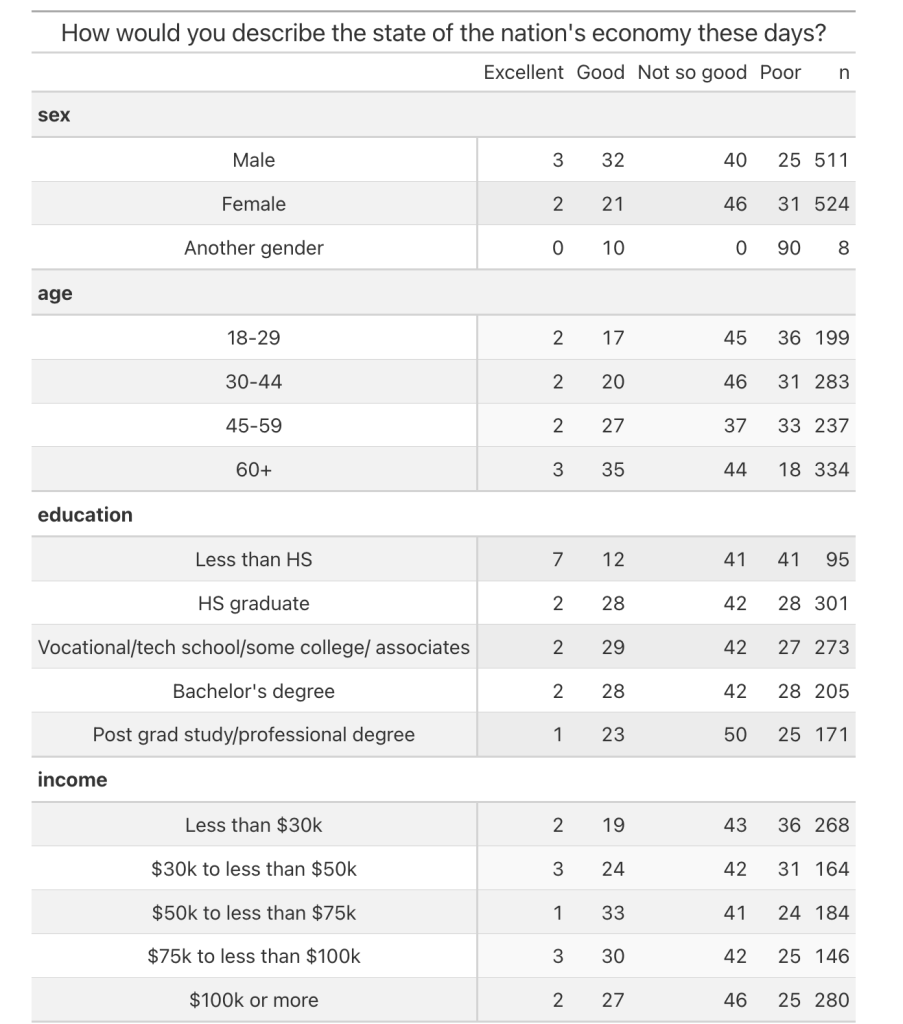

I’ll cherry-pick the latest Marquette University poll, since they’re my favorite: in most polling, a majority of respondents say the national economy is terrible, but also that their personal situation is about the same or better.

Here you can see 72% of American adults say the national economy is bad, but not all of them think they are doing badly themselves on the latest Marquette Polling battery.

It’s fair for liberals, conservatives, leftists, and neo-fascists alike to wonder: “What is going on here?” At some level, one would expect opinions about the economy to track the actual economy, or even some level of personal well-being. Not anymore. After decades of economic sentiment surveys, something has broken beyond what can be fixed by marginal tax rates and welfare state tweaks. Does the real economy matter anymore, or is everything perception and partisanship?

Eternal Vibescession of the Spotless Mind

1. The Right Profile

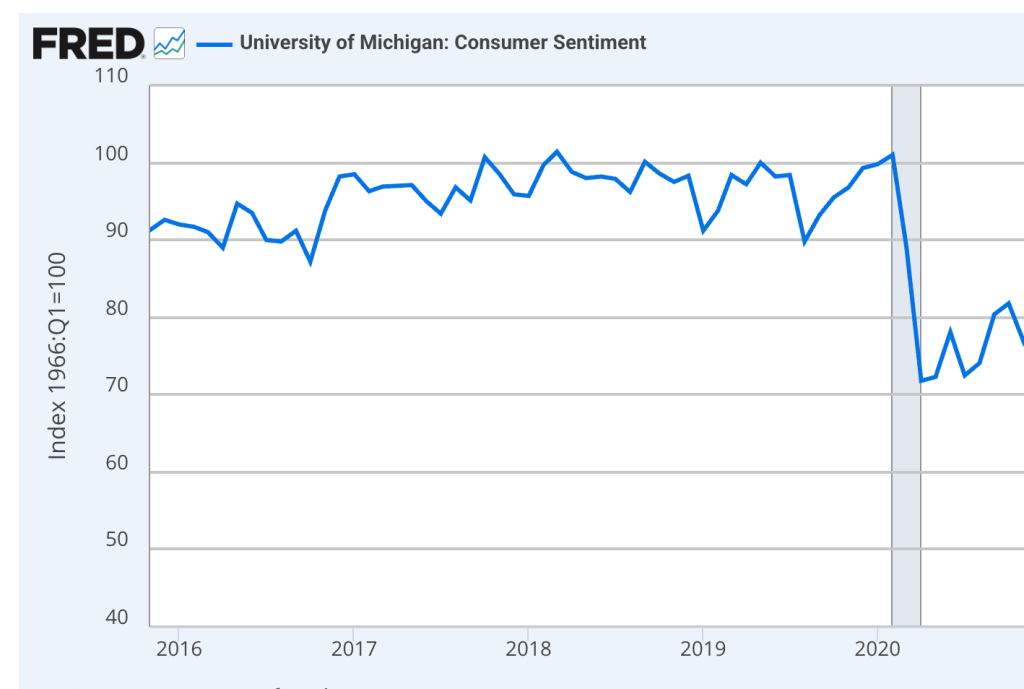

Since 1953, the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index has accurately tracked sentiment going down during recessions and up during expansions.

Don’t like the Wolverines? The same general effect appears in The Conference Board Consumer Confidence survey. And why wouldn’t it? If unemployment is high, inflation is rampant, or growth is sluggish, then people should respond accordingly.

In contrast, 2025 has seen widespread dissatisfaction with economic conditions despite the underlying economy being mostly fine. Critically, this is a clear continuation of the trend established during the Biden administration, where consumer sentiment tanked after the 2021-2022 inflation wave and never recovered, despite no apparent slowdown in growth or employment.

All of this has come as a nasty surprise. In the Edison Exit Poll, 53% of voters thought Trump would be better on the economy, compared to 46% for Harris (a clear overperformance of Trump’s popular vote margin, implying Harris won voters who were skeptical of the Democrats’ economic record). All of Harris’ warnings of recession, tariffs, and chaos were ignored. 68% of voters thought the economy was “Not So Good” or “Poor”. Voters in 2024 who reported negative economic sentiment backed Trump 70% to 28%. For an incumbent party, those are not good numbers, and the Democrats duly paid the price.

There were plenty of reasons to expect economic sentiment to reverse. For one, this appeared to be a return to the familiar “economic anxiety” narrative of 2016, when the same Edison Exit Poll reported Hillary Clinton lost voters who thought the economy was “Poor” by 62% to 18%. In a few months, those voters magically started referring to the economy as “Good” and Trump held strong approval ratings on the economy until the COVID-19 Pandemic in March 2020. This sudden reversal made it seem the economy was merely a cover for other concerns.

“Large numbers of voters who in early November declared themselves in such surveys as the monthly Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index to be miserable about their financial circumstances will feel better about their affairs,” the historian Adam Tooze noted in his 2024 retrospective.

All the partisan Republicans would simply switch sides with Democrats, and enough independents were willing to give Trump decent marks to have it wash out. As long as the economy was showing solid growth and consumer spending numbers without substantial inflation, voters would continue to give a Republican president (ungrounded) credit for being “pro-business” and cutting taxes. What could go wrong?

2. Straight to Hell

There is an unstated belief among the media and political class that the Americans gained any optimism on the economy when Trump was inaugurated in January 2025. This is not true whatsoever; people are confusing Trump’s approval rating on the economy with actual opinion.

(As a data note, I will be using a lot of charts from ElectionCord’s crowdsourced polling average. If you are dubious of the chart, here is the source spreadsheet containing the toplines and many crosstabs to literally every poll taken this year.)

To start Trump’s term, around 70% of voters thought the economy was bad. We closed the book in 2025 at…69% of voters thinking the economy is bad. That’s not much change over time, to say the least (the start of 2026 has not been better).

Looking at the chart, there’s little use in tying causation to certain events or headlines. Perhaps the polling got worse around August 2025, which does coincide with the enormous tariffs announced on Liberation Day being officially implemented on August 7. But that’s just a guess. Everything that has happened since economically—a 100% China tariff that tanked markets, the government shutdown, and further perceived chaos has not engendered much improvement.

As we must caveat in every public survey these days, yes, there are strong partisan effects. The out-party immediately started “expressive responding” and reported that the economy was bad. In addition, the type of moderate Democratic voter willing to give Trump the benefit of the doubt on the economy, which had existed in his first term, has completely disappeared. Thus, Trump was always going to start with worse economic ratings the second time around, but, as with most things regarding the administration, it has been much, much worse than expected.

Trump entered office with a small approval “lead” on the economy, but it quickly dissipated even before the great “Liberation Day” tariff announcement that crashed the stock market on April 2. As you can see by the totals, Trump’s lead on the economy came with only about 80-85% answer rates, which implies about 10-15% of Americans were willing to wait and see what happened before giving a verdict. As the year progressed, the verdict they gave was overwhelmingly negative. In addition, a significant number of Republicans and softer independent voters have also soured on Trump’s economy, especially after the repeated tariff fiascos.

This chart looks similar to views on Biden’s economy, with the tariffs replacing the 2021-2022 inflation shock.

When looking at the issues collectively, Trump’s rating on economic issues are markedly worse than anything else. Indeed, despite the recent focus on immigration, the murder of Renee Good, and the Minneapolis occupation, Trump remains substantially more popular on immigration than on anything else.

When looking at “the trend of the economy”, the picture is just very grim for the administration. For most of the year, a steadily growing majority of respondents think the economy is getting worse.

The negative responses are coming from the groups that swung hardest against Biden: young people, Latinos, Asians, and voters below the 50th percentile in median income. You can view these crosstabs in our poll tracking page (scroll down a bit).

The world forgetting, by the world forgot

If you are reading an in-depth article about public perception of the economy, you likely know that the U.S. Economy has not completely collapsed. There are very few red flags in the underlying economic data outside of human-reported sentiment. As mentioned earlier, many reports show strong growth. What about commodities? Retail gas prices have fallen to under $3.00. Food inflation is around 3% YoY. That’s annoying, but manageable.

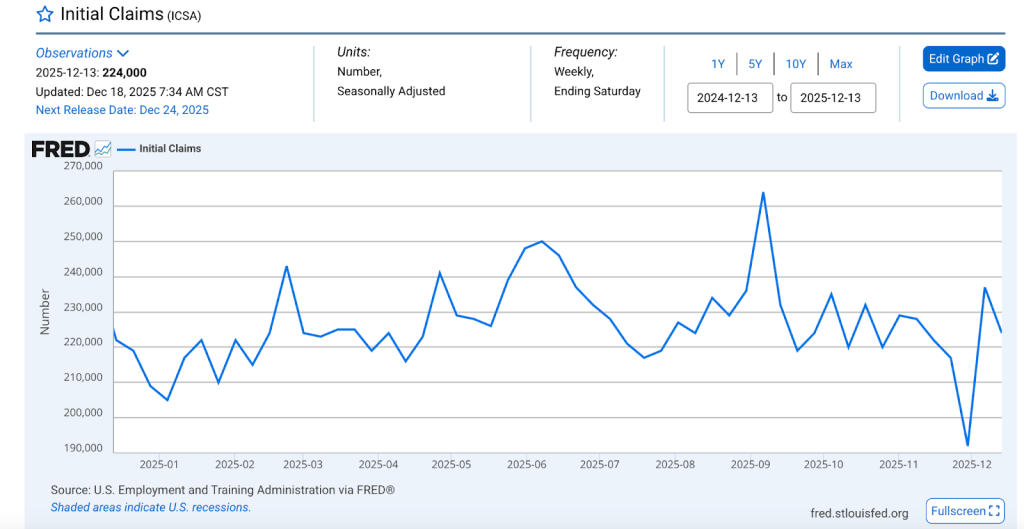

Then we have the labor market, which is the biggest sign of weakness outside of tariffs. Still, it’s not indicative of a severe recession. Unemployment has risen by 0.5 points since the start of Trump’s term to 4.6%. That’s bad, but not recession-worthy. Initial unemployment claims over the year have been flat. Job growth is slowing and that could be a major issue as we go through 2026, but it shouldn’t have affected 2025.

I’m beating a dead horse here. We know economic sentiment has become “vibes-based”. Yet policymakers and politicians have to now seriously account for perceptions of the economy mattering more than the real economy. Since we’ve been at this for close to three years now, we should expect the poor sentiment to continue until morale improves.

Affordability Unto Death

Maybe the economy is that bad! We have dozens of charts and a lot of anecdotal social media posts saying that the economy is in shambles and no one can afford anything. Indeed, it’s impossible for any figure to note positives on the economy without being hit with a dozen accounts saying, “HOW DARE YOU?! I JUST PAID $115 FOR TACO BELL?!” This has been the case since at least 2022, and the new administration has seemingly been blindsided by the continued fury.

Trying to fight the tide has gone poorly, especially since the new tariff regime gave every American a scary one-word policy to blame rising costs on. In addition to collapsing in polls on the economy, the Democrats swept the 2025 election cycle with affordability messaging, pouncing on a weakness the Republicans exploited to great effect just a year earlier.

In Paul Krugman’s series on affordability, he identified three explanations for why this is occurring.

- Housing affordability and social inclusion – basically, the American Dream is to own a house, and young people can’t afford houses.

- Economic insecurity – people are afraid they’re going to lose their jobs or have an unexpected life downturn.

- Fairness – people are mad that billionaires and profiteers are succeeding at their expense.

All fair, but the fact remains that economic sentiment is even more disconnected than these underlying factors would suggest. These numbers are what we’d see during a general economic depression, not the constant battle for the American dream. In the latest GDP print, personal consumption has made up the largest share of economic growth this year (e.g. people are spending money).

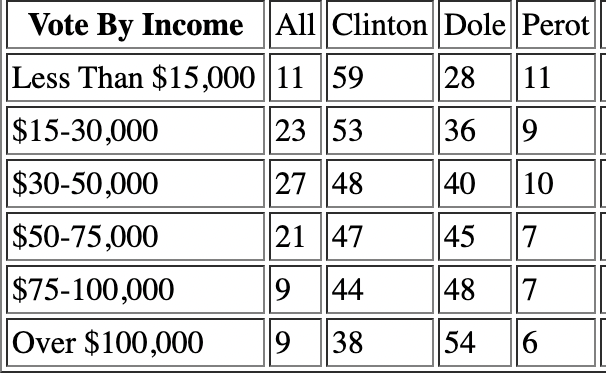

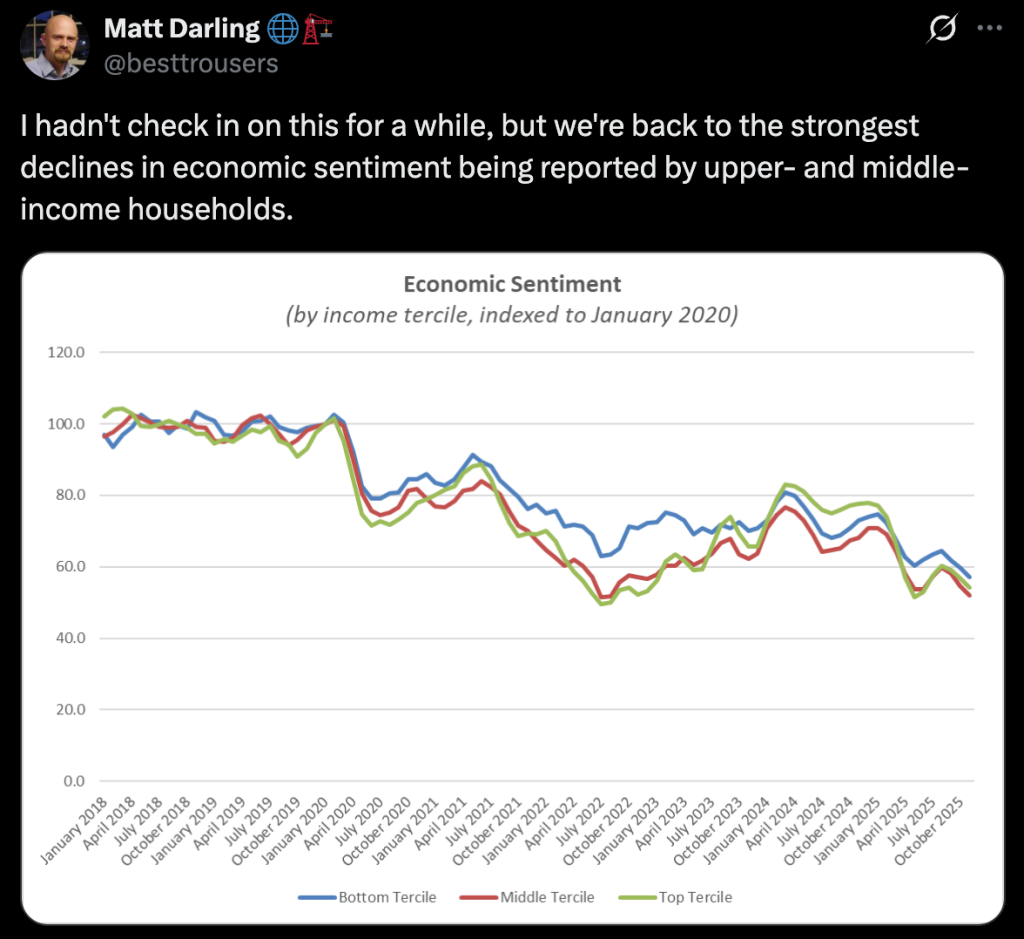

Then there’s the argument of the “K-shaped recovery” where only richer consumers are able to spend and enjoy the fruits of the economy. Yet richer Americans actually report worse economic sentiment than poorer Americans, just as they did during the inflation wave of 2022-23.

Jason Furman is a controversial figure for some, but his point that real wage growth has been solid across income levels tracks with data. If there is a K-shaped recovery, it hasn’t shown up as much as one would think.

As some polling confirmation, you can see the latest Marquette crosstabs, which confirm the UMich sentiment is not an outlier. There’s almost no difference between income groups and economic negativity. If anything, due to partisanship, the middle-income voters produce slightly better ratings of the economy.

Is this about the famed American Dream? Well, home and rent prices this year have actually stayed flat or dropped in many areas, making shelter slightly more affordable than last year. Americans are buying more cars than ever! Again, something’s not adding up.

Being a little dumb, as a treat

While some of the explanations posited must be taking a toll, it still can’t explain the full picture of economic perception outweighing reality. For one thing, it’s worth wondering whether “vibes-based” political economy is something we want. The notorious Will Stancil recently opined on Bluesky that if consumers are going to demand to switch the government every two years based on 2.5-3% inflation, the entire progressive project should give up. Indeed, any ideological project would collapse on impact if it hit -20 approvals within the first six months. That isn’t enough time to complete a baseball season, let alone make transformational changes to the United States.

Indeed, Stancil has become something of a poster child (emphasis on poster) for the idea that voters are simply lying or deluding themselves into making political decisions based on the economy, and that the severe thermostatic backlash of the post-2020 period is based on social media. In this way, we have actually reached a post-material society, and culture war is all that matters (a war that the Democrats had been losing in 2023-24).

This argument is always inevitably followed by the aforementioned crowd of people who say they spent obscene amounts of money on healthcare, car parts, lawn care, childcare, Bloomin’ Onions at Outback Steakhouse, and everything in between. And that is also, in its own way, undeniable.

Yet the economy has to be important somehow, or else we wouldn’t see repeated claims from voters that it is their most important issue. To me, the heart of the issue is that the economy has become just another front in the post-2020 war over American society. The primary economic questions are not about overall growth, but increasingly zero-sum debates like “Is this fair?”, “Who gets what?”, and “Am I being screwed over?”. Ideological orthodoxy, especially on the left-to-right axis, is increasingly rare. Which is to say that if you can rile people up that immigrants are screwing them over, you can just as easily rile them up about Trump’s cronies screwing them over. And with the pace of social media, you can achieve a rapid thermostatic backlash among the small group of swing voters that matter and persuadable soft voters on the other side.

It’s well known that news companies get more views for producing negative material in general, and the economy is no different. Then there’s a network effect, via LinkedIn, Instagram, and other social networks, we can see more people that are struggling (I can’t tell you how many times on LinkedIn a post has gone viral of someone who can’t afford bills and needs a job). Meanwhile, total lies take off without anyone fact-checking.

Some greatest hits:

- All economic growth and investment is in AI, which is also sucking up all the water, don’t you know?

- There have been mass layoffs everywhere.

- Young people are in bread lines and trading in their comp sci degrees to work at Chipotle.

- The immigrants are taking the money (this was very popular in 2023-24).

- The eternal promise of “stimulus checks” that go viral when they’re not happening, and the eternal disappointment when the date comes and no check arrives.

- Trump is stealing all the money and sending it to his buddies (well, at least that one is partly true).

In this way, Trump’s prolific content generation is actually hurting him; he can’t effectively communicate his message like Biden, and thus, he also keeps creating a negative economic perception. Tariffs were the worst possible policy for Trump to pursue, not because of stupidity or regressive effects on household income, but because it quickly became a catchy idea to express economic discontent. Viral videos, memes about stock portfolios crashing, and eBay shipments that cost $1,300 were more damaging than the actual economic impact. No one could explain what the tariffs were for (certainly not Howard Lutnick), so voters made up their own reasoning (it was to hurt me, the main character of reality). We can then extrapolate to occupying Minneapolis as a way to create a different narrative for the administration.

Good luck trying to create one with economic data. Echelon Insights asked a fun question in its last poll and found 47% of Americans do not trust the government’s economic statistics. Just 28% answered that they do.

It does raise the question of whether 2020 raised some sort of psychotic breakdown on social media, where the endless series of algorithms went all-in on negative content and never looked back. And perhaps we need to restrict social media and de-emphasize the nonstop belief that “my success is being limited by [insert group] I saw on Instagram Reels”. But this is the world we live in, and right now Democrats from Zohran Mamdani to Abigail Spanberger are reaping the political benefits.

See, nobody cares!

From a political perspective, the polling data and election results suggest that this argument between “lived experience” and economic data doesn’t matter at all. After all, the economy is another idea haphazardly bouncing around people’s skulls. There is nothing policymakers can do to force voters to stop saying “why’s this sh*t SO expensive?”.

This has been matched in polling and election results, where Trump has lost the most ground among less-engaged voters. The less engaged you are, the less you care about a party’s ideological bent, and the more you care about economics.

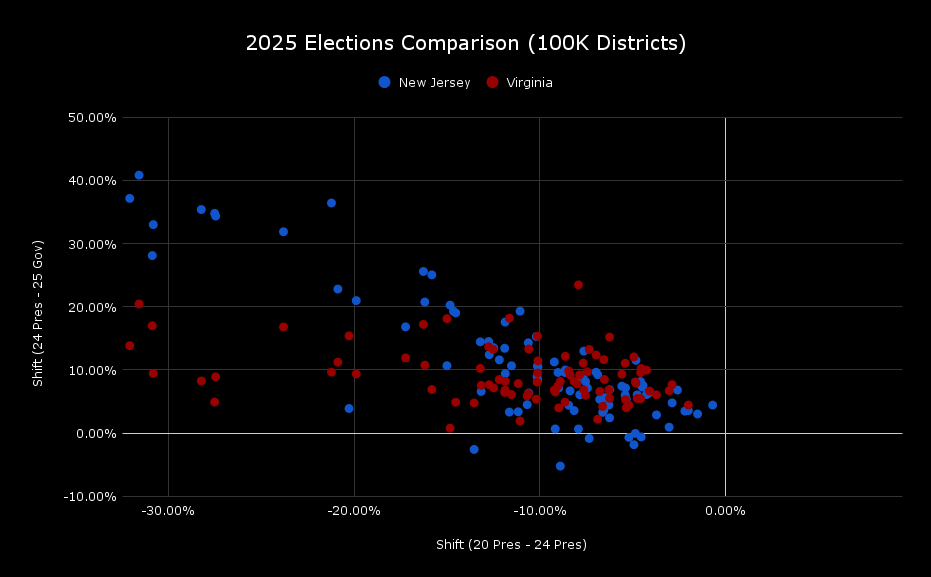

Wherever Trump made gains among “softer” voters in 2024, he has since seen the largest declines. Here are the results from the Virginia and New Jersey Gubernatorial races divided into blocks of 100,000 people (e.g. think of them as a large precinct or county map). The areas where Trump swung voters to him in 2024 are the ones that defected to the Democratic candidates in those two elections.

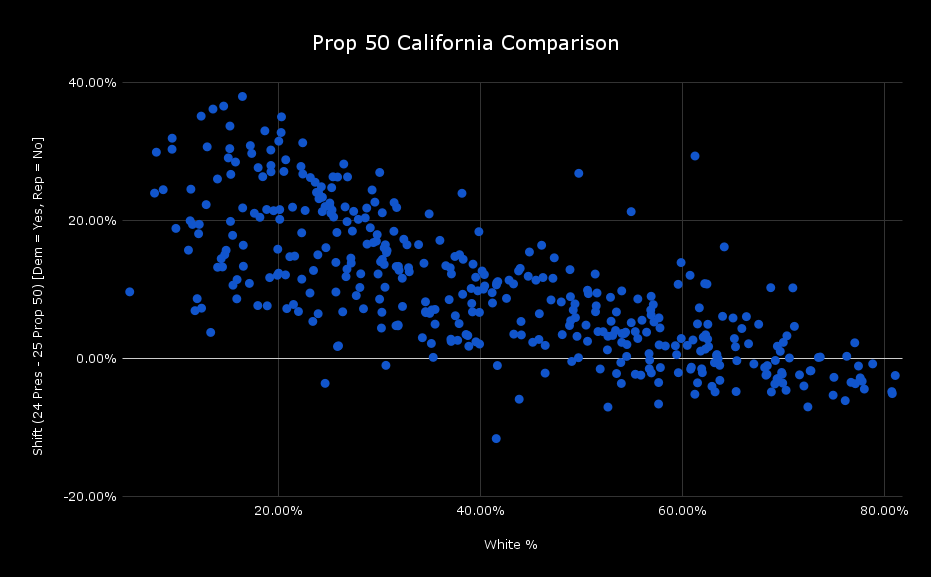

In California’s Prop 50 referendum, Democrats gained the most support among nonwhite areas, many of which had swung right just a year earlier.

While these types of analyses are not perfect, they do broadly match what we’ve seen in the polling. Voters are willing to punish the incumbent administration for something, and similar to Biden, it appears to be about household economics.

Vibescession International?

The question turns to whether politicians can manage economic perception. For that, we can try to look to non-American examples, although these are also difficult to parse. In the OECD, there are examples from the left and right of politicians who have been able to weather the bad vibes. And then there are examples from the left and right of those who haven’t.

Canada: After withering unpopularity forced out Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, former central banker Mark Carney has taken over the Liberal Party of Canada and led them to a historic comeback in the 2025 election. Carney’s overall approvals remain strong despite an economy that doesn’t appear to be outperforming peer nations. Perhaps this is a legacy of his time as Canada’s “savior” during the 2008 recession and his reputation of competence, but his ability to weather the headwinds is undeniably impressive. Carney is significantly more popular than the Liberal Party as a whole, giving him wide latitude to propose policies and take credit for wins.

While some may argue that Carney’s stellar reputation will drop over time, he has already held popularity on economic issues for much longer than Trump, Keir Starmer, or dozens of other leaders.

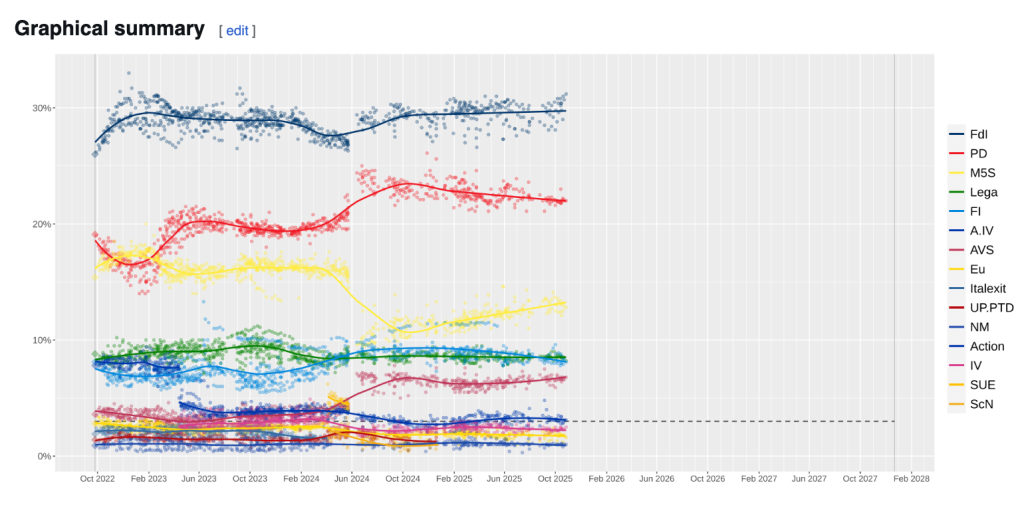

Italy: In Italy, hard-right leader Giorgia Meloni has defied expectations. In a Europe where leaders like Emmanuel Macron and Olaf Scholz frequently test the -50% range, Meloni has managed to hang on to mid-40s approval ratings. Her Brothers of Italy (FdI) party still maintains a solid polling lead three years into her first term as Prime Minister. Meloni hasn’t been able to stay net favorable, and there have been some gains from the Italian left, but she has so far avoided the total electoral collapse of other leaders.

Is this because Italy has achieved its strongest economic growth in years and Meloni has governed far more as a “normal” right-wing politician than as a neo-fascist loon? Do they not have Internet in Italy (and Canada)? It’s unclear.

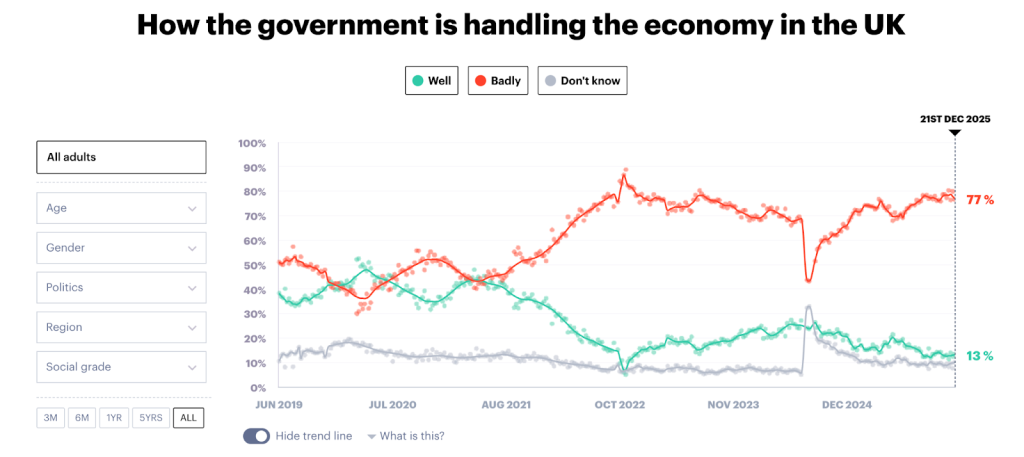

United Kingdom: Sentiment in the United Kingdom looks very similar to the US, despite undergoing the opposite shift from a right-wing government to a left-wing government. Both the Johnson/Truss/Sunak Tory governments and the subsequent Labour majority government under Keir Starmer have had awful favorables on the economy since.

Because the economic situation is worse in the UK, perhaps their numbers are a little more justified. However, given that there hasn’t been a sudden shock in unemployment or a recession since the pandemic, it’s easy to see how some of this negativity is also bad vibes driven by social media.

It’s the stupid economy

From these examples, it’s possible that a less divisive and more trustworthy politician could deliver better economic messaging and overcome perception. But in some sense, the communication issues are almost irrelevant. It’s not that politicians are uniformly incapable of communicating their message—it’s hard to imagine a president can have more attention than Trump—it’s that the public refuses to buy anything. For all we know, the latest crop of “affordability” politicians will be tossed aside by voters the next time around.

Call it a zero-sum attitude, blame whatever generation you tend to hate the most, but the overall picture is one of voters no longer noticing certain macroeconomic effects. It appears we have now been divided into two rock-ribbed ideological parties, and a huge middle of people who feel like they are falling behind.

The solution may be a magic adjective that many feel is in short supply: competence. In a time of constant dissatisfaction, any appearance of competence or, gasp, actual competence can be the only thing that cuts through the noise. If what’s occurring in the 21st Century lies outside of the traditional left-right divide, accomplishing anything whatsoever seems like a success worth keeping.

Consider the example of Josh Shapiro in Pennsylvania, who retains sky-high approval ratings despite entering his fourth year in office. Stripping away ideological concerns, people feel that he is a capable governor, even around 1/3rd of Republicans. That might be the only way to avert the current curse of incumbency. It’s also something Donald Trump is completely incapable of doing at present. With just 10 months to go until the midterms, we can only expect opinions on the economy to stay the same or get worse.