One of the key stories of the last decade of American politics has been the realignment of poorer voters with Donald Trump’s MAGA movement. Even if arguments continue to rage about whether the Democrats have made inroads with wealthier voters (answer: yes, but not as much as you might think ), there is little doubt that there have been significant losses among poorer voters across all segments of society. From The New York Times comment sections to the microblogging platform of your choice, seemingly everyone has an opinion and a clear-cut reason for why Democrats are losing “the average person”. The answer is usually “whatever I happen to be annoyed about on any given day.”

That being said, it’s worth taking a moment to understand the context and stakes of the problem at hand. Since most of the people commenting are in elite circles to begin with, it’s easy to ignore basic electoral realities and hard data that confound the narrative. So, consider this an introductory guide to analyzing elections through income inequality.

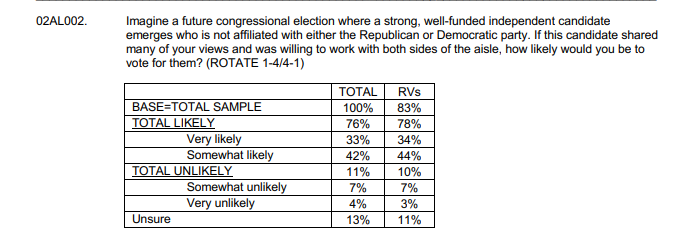

For at least two generations, the Democrats were widely seen as the standard-bearers for disadvantaged people in American society. I’m using the 1996 exit poll as a convenient chart, but you can essentially replace it with any exit poll going back to the 1960s and find more Democratic support among the lowest-income groups. This trend was essentially true all the way up to the 2012 presidential election. Even in Reagan’s landslide over Walter Mondale in 1984, Democrats won those making less than $12,500.

The reasons for this linear trend are well-established. Starting with the New Deal, and then continuing with the Civil Rights Act and the Johnson presidency, Democrats were seen as being the party that helps those less fortunate. In the shadows of Democratic dominance of the 1930s, Republicans gradually became the party of wealthier voters attracted to the vision of “Rockefeller Republicanism” formed in the wake of their defeats in the 1930s. After the realignments in the Civil Rights Act, this picture shifted. The Democrats retained support among poorer voters, but now they increasingly relied on:

- Black voters

- Other minority voters

- Holding their own with poorer whites (with the help of unions)

From 1960 to 2012, American elections were fought over the swing-voting middle class, most of whom were non-Southern Whites. Democratic fortunes were often determined by how well they could turn out poorer voters. Throughout every form of electoral democracy in the history of the world, the poor participate less than the rich.

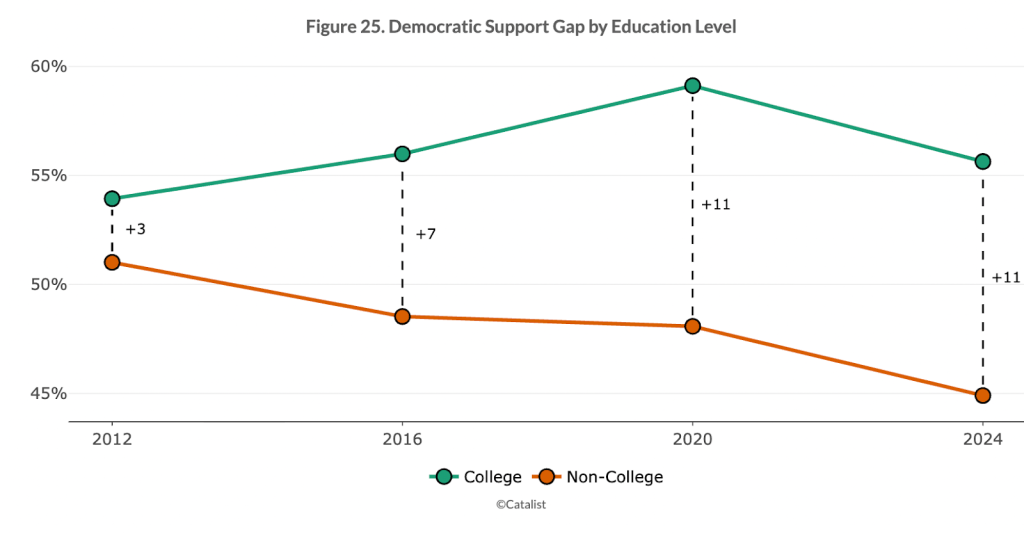

So, what happened? Well, in 2016, Donald Trump and the Seventh Party System took hold, and the United States has been undergoing an enormous realignment along educational and cultural lines. This has led to Democrats losing their sizable advantage among poorer voters, while gaining an outright majority among the wealthy, a reversal of trends going back to before women were allowed to vote.

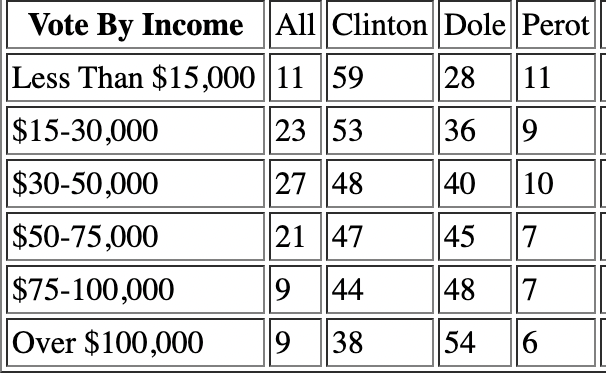

The Edison exit polls now show a U-shaped curve, with Democrats narrowly ahead among those making less than $30,000 and those making more than $100,000. It should be noted that none of these margins is very decisive.

Now, these exit polls are not necessarily gospel, and these numbers have bounced around in ways that don’t make a ton of sense. In 2020, CNN/Edison found Biden made improvements among the poorest voters, and they made a larger share of the electorate than in 2016 or 2024. There is some precinct data that matches this, but other data is conflicting. Sampling poor voters is notoriously difficult, and it’s hard to get a full grasp on how they’re shifting over time.

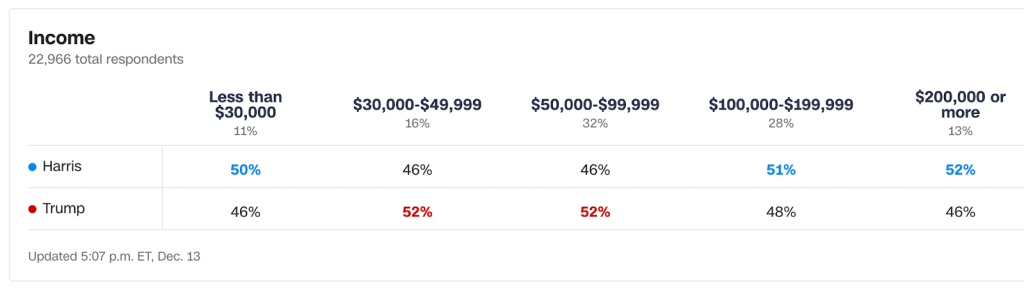

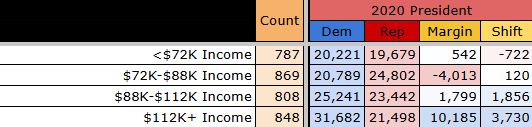

The ElectionCord 100K District Project, where each part of the country is cut into different subsections of 100,000 people and then analyzed based on demographics, found different results from 2016 to 2020. There was a clear shift away from Dems among poorer districts, and a shift toward Dems in richer districts.

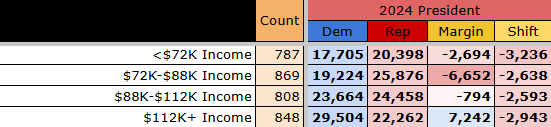

By contrast, the 2020 to 2024 comparison saw shifts against Democrats across income demographics, with their heaviest losses among poorer districts. Interestingly, the second-largest shift came in the richest 848 districts, even if they were the only grouping that Democrats were able to win.

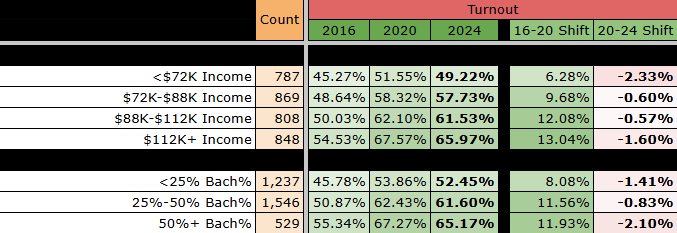

There’s a misconception that education/class/income polarization *increased* in 2024 relative to previous years. However, data from the 100K District Project and external exit polls indicate that further polarization did not occur. Rather, the Democrats lost ground everywhere. In both education and income, the wealthiest and most educated voters did not move significantly further left in 2024, unlike 2020. While there were slight differences, none of the differences in income group shifts matched what happened in 2020. Harris only did slightly worse relative to the mean in poorer areas, but in 2020, Biden did much better relative to the mean in richer areas and much worse in poorer areas.

Indeed, the wealthiest and most educated populations saw a larger drop-off in raw vote turnout than “middling” groups. This cost the Democrats in safe blue states, but likely didn’t cause them to lose the swing states where turnout levels remained elevated. As a result, Democratic vote losses primarily took place in areas where turnout dropped more, which speaks to their unpopularity (trying to determine between turnout and persuasion here is difficult—they were likely linked since those are the main cohorts of the Democratic coalition).

Catalist confirmed that while the absolute gap in education levels (which we’ll use as a proxy for income for now) stayed at +11 in 2024, the same as in 2020. There were large increases in 2016 and 2020, but none in 2024; Democrats lost ground with college-educated and non-college voters.

There are glass-half-full and half-empty ways to interpret this. One could argue that, despite the Biden administration’s perceived failures, the 2021-2024 period did not increase education polarization, giving Democrats an easier pathway to regaining votes rather than experiencing the realignments of 2008-2020. On the other hand, their inability to reverse education polarization by improving with non-college voters has left them uncompetitive in key Senate seats. In addition, they lost ground even with wealthy and educated voters, due to turnout issues or genuine persuasion.

All of this paints a complicated picture. The Democratic Party is simultaneously filled with champagne socialists, but also commands better margins among the poorest voters. Meanwhile, Trump dominates what I call the “middle 60%” (the people in the 20th to 80th percentile on most household income surveys).

Cause and Effect

With the electoral mechanics out of the way, it’s time to evaluate why these changes are happening. I’ve identified three popular hypotheses about why the poor are leaving the Democrats, and tried to evaluate the evidence for each.

The Media Hypothesis – The Poor Are Getting A Steady Diet of Right-Wing Slop

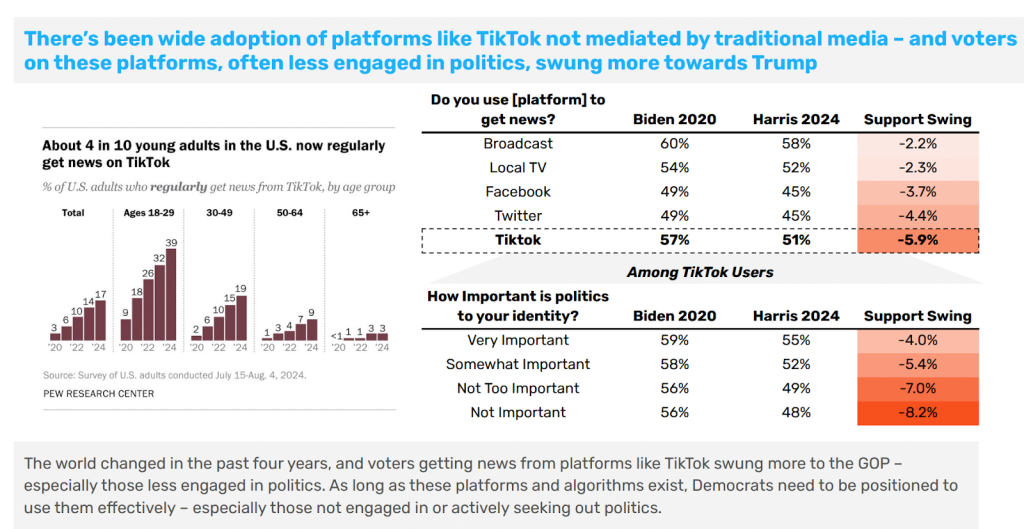

- Favored by those in the media for obvious reasons, there is a persistent belief that changing media habits and the end of “mainstream” media have swung disengaged voters away from the Democratic Party, even going back to 2020.

- Biden’s poor communication skills and failure to take control of any narrative gave the right free rein to generate unfavorable media. On issues as diverse as grocery prices to the Israel-Hamas War, right-wing narratives took hold and pressured voters to defect or sit out.

- This chart by David Shor’s Blue Rose Research shows larger swings against Harris from those who used TikTok and Twitter rather than traditional media.

- As a result of this failure to reach disengaged voters, Democrats have lost ground among the poor, nonwhite, and younger voters that they used to rely on. As a replacement, they have gained older and more educated voters who watch the nightly news. This theory has been championed by David Shor and many other leading Democratic experts.

Flaws in this theory:

- Why did richer voters also desert Democrats? No one has answered this. It would require another article.

- Issue polling shows poorer voters prioritized economic concerns, while media coverage largely centered around Republican culture wars. If anything, it was Trump’s ads focusing on the economy that may have made more of a difference rather than media engagement.

- Biden’s failure to reach poorer voters in 2020 suggests that this was outside the bounds of the 2024 environment and speaks to structural issues noted in the other two theories.

The Class Conflict/Materialist Hypothesis – The Democrats Have Lost Touch With the Material Interests of Poor People

- Common among those on the populist left and right, this thesis is basically an updated version of the 2016 Hillary defeat, just involving nonwhite people instead of the white working class. It’s Thomas Piketty’s “brahmin left vs. merchant right” thesis: Democrats are too woke and only care about social issues, so the poor desert them in favor of the opposition or don’t vote at all.

- During the Biden administration, poorer voters were faced with higher costs and a perception of rising inequality. The theory suggests they found the administration’s focus on “irrelevant” issues like climate change and social justice to be insulting and punished them accordingly.

- In this case, ads like “Kamala is for they/them” reinforced the idea that Democrats had gone too far to the left socially and no longer represented working-class voters. On issues like immigration, LGBTQ rights, and energy, poorer voters were no longer in line with what Democrats had to offer.

- From the populist left, a perception arose that Democrats were once again bowing to corporate interests and big donors.

Flaws in this theory:

- The economic situation for poorer Americans immediately after the COVID relief programs was substantially better than before, but Biden’s approval rating started dipping before the inflation wave happened.

- Biden went out of his way to accommodate unions and other pro-worker options, but received no credit for it.

- The Democrats still won the poorest voters (largely because they continued to win nonwhite voters, despite what many pundits have said). This suggests that poverty itself is being moderated by culture, economics, and race; rather than a full inversion, we see a U-shaped curve as the Democrats have a coalition of the very rich and very poor.

- Going back to the ElectionCord data, we see that Democrats’ biggest electoral liability is not the poorest regions, but the regions in the second quartile ($72-88K income), where they have continually gotten crushed since 2016. This suggests the Democratic failures are not tied to poverty, but rather the perception that these voters have been “cut out” or “left behind” as the rich have realigned toward the Democrats. More concerningly, these groups tend to vote at much higher rates than voters who are in the first quartile. In 2024, the $72-88K districts’ overall turnout was 8 points higher than the <$72K. The average Trump-won 100K district saw a turnout rate that was 9 points higher than the average Harris-won 100K district. In 2016 and 2020, the average Trump-won district had a turnout rate of just 5 points and 6 points better than the Democratic-won district, respectively. Given that these were clustered in Democratic strongholds, it’s hard to ignore that these specific turnout declines hurt Democrats.

- Not to get into the “would nonvoters have voted for Trump” debate, but given that we are talking about nonwhite nonvoters in the most Democratic-friendly areas, they likely could’ve helped Harris stay closer in the popular vote. Perhaps nonvoters overall (which would still be majority White, by the way) would have voted for Trump narrowly, but in this differential turnout discussion, that’s less important.

The Thermostat Hypothesis – The Poor Reacted Negatively to the Incumbent, Same As Ever

- It’s not as if Democrats weren’t trying to win over these voters, but maybe they weren’t listening. The Thermostat Hypothesis implies these failures are out of Democrats’ control; the post-COVID malaise, the inflation wave of 2022-2023, and geopolitical tensions can hardly be attributed to one political brand. But without a convenient way to pass the buck, poor voters have heaped scorn onto the Democrats, even as they vote (or sit out) to enable policies that directly harm them.

- Thermostatic opinion is real and powerful. It’s rare for politicians to avoid thermostatic backlash—Obama certainly wasn’t able to avert its power—and one would assume some backlash against a Democratic administration, especially one that was unpopular. Already in the second Trump term, the government and its policies have poor favorability ratings. Those who were drawn to the opposition have less fervor, and those in the opposition are now able to win over previous skeptics and activate new disgruntled members of society. The pendulum swings back.

Flaws in this theory:

- The backlash against Biden was unusually large, even greater than the one against Trump in 2020 and every president going back to George HW Bush.

- Harris’ defeat occurred despite the Democrats having a decent midterm result in 2022, implying that some element of “hard-to-reach” or “low-propensity” voters disliked Democrats who weren’t involved in prior thermostatic backlash.

- Replacing the candidate did not lead to a large recovery for Democrats, and it’s unlikely Gavin Newsom would have done much better than Harris given publicly available polling.

In the end, it’s easy to see some truth in all three hypotheses. Without a mass mind-reading device, it’s impossible to fully understand which explanation is working on which people at any given time. My money would be on a mix of class conflict and thermostatic backlash, but there are compelling reasons to evaluate the left’s media posture or external factors (foreign policy causing inflation, etc).

Why does any of this matter? At the end of the day, if democratic institutions survive in this country, the majority of the electorate (59% on exits) makes less than $100,000 per year. Even though richer voters punch above their weight (>$100K was 41% of the electorate vs. 34% of the country), losing poor voters is still a bad trade, and also antithetical to what Democrats often profess.

In a way, the Republican coalition is very well-suited to Trump’s populist brand; he represents a segment of the income scale that has fallen vastly behind the richest 10%, but maintains a higher standard of living than “the poor” (read: Black, Latino, and recent immigrant families). On the other side, many Democrats now find themselves in the awkward position of indirectly benefiting from many of Trump’s policies that will exacerbate inequality, while the poorest are made to bear the costs of Medicaid cuts and tax breaks for the wealthy. Still, policies like “no taxes on tips” and reduced tax enforcement certainly stand to benefit the “middle 60%” that Trump has drawn to his side.

For now, this phenomenon appears to be a Trump-only situation. During the 2018 and 2022 midterm elections, as well as special elections and off-year contests, the poorer/younger/less white/[insert Democratic characteristic] voters that do turn out tend to be more left-leaning. The 2022 midterm performance for Democrats among these voters was in line with historical averages, with turnout being the main dragging factor. Meanwhile, 2016, 2020, and 2024 saw an army of low-propensity, 20-80%ile voters show up only to vote for Donald Trump. Is this sustainable, or is it merely a temporary blip? We don’t yet know.